Alex – Intel’s Larrabee

Since Larrabee – Intel’s now permanently delayed visual processing unit – hasn’t actually shipped you might think it’s either completely obvious or completely redundant to pick it as the failure of the year. Already slain by its own family, why give it another kick?Well, it’s not the actual chip I’m nominating – after all, aside from a disappointing demo, it remains an unknown quantity. Larrabee performance numbers haven’t been made public, and we’ve not tested the chip for ourselves.

Really what I’m nominating is everything else about the Larrabee project: the delays, the games industry's lack of belief in ray-traced games and Intel’s public war of words with Nvidia. It’s a heady brew and it resulted in the most high profile failure for the x86 architecture we’ve yet seen. In fact, it’s possible Larrabee’s cancellation is instructive about some of the major challenges Intel is going to have to face in the next few years.

And no, AMD fans, I don’t mean Fusion, Bulldozer or whatever long-promised project the joint AMD-ATI might or might not get round to releasing. I mean the fact it’s increasingly clear that unlike the old days, Intel can’t simply click its fingers and have the IT industry follow suit. The cancellation of the first Larrabee illustrates Intel’s inability to move beyond its core competency of x86 CPUs.

Intel recognizes that selling desktop and laptop CPUs to end users in the developed world is a fairly flat market, and so is questing to find the next billion users – and yet its failures at finding these users are becoming more and more noticeable.

First, there was its failure to get mobile phone manufacturers to give up on ARM CPUs, and then its increasing wariness of bargain basement netbooks, banishing Atom to be made by TSMC and attempting to upsell people to CULV chips. So, Intel looked to get x86 into the world of game graphics and physics, with one eye, of course, on the big payday of getting into the PlayStation 4 or the next Xbox.

Yet Intel couldn’t even get out of the starting gates by hitting its own deadline. When it comes to CPUs, Intel has a decent reputation for sticking to its roadmaps. It makes a good amount of information about its future direction public (the tick-tock strategy, the ambitious plans to forge ahead with new manufacturing processes) and in recent years it’s more than delivered on its promises – it’s not unheard of for us to have samples of new CPUs three months or more in advance. Given that you get generally get a week (or at most two) advance time with a new graphics card ahead of launch, this is a stunning achievement. When you consider that Larrabee was first officially acknowledged in 2007, and that we waited until 2008, then 2009 and now who knows when to actually see it gives you an idea of how uncharacteristically badly the project went.

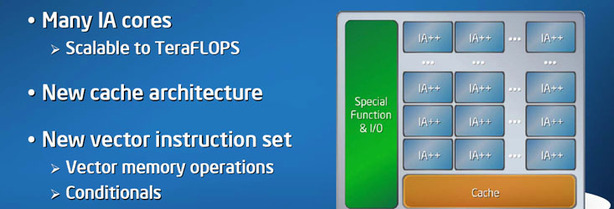

The Larrabee project illustrated that Intel couldn’t just march into the world of gaming and get everyone to change to suit its wishes. The idea of a big bundle of old x86 cores proved to be something the games industry was divided over – for every Tim Sweeney who loved the idea, you had another set of developers who were quite happy with existing rasterisation techniques, and of course, bottom-line-focused game publishers are extremely wary of sanctioning any extra spend on PC games graphics.

With the existing games consoles using traditional PC graphics chips, new ones are a long way off (for reasons we went into in ourIs Console Gaming Dying? feature) and Microsoft is obviously reluctant to re-write DirectX so soon after the DX10 reboot, it’s not surprising Larrabee failed to generate any critical mass. Two-and-a-half years after first talking about it and all Intel could muster was the same old ray-traced demo of an id game, stuttering along on a next generation CPU.

The inertia of the gaming market wasn’t the only thing Intel misjudged – it also got suckered into playing Jen-Hsun Huang’s PR games. Despite the fact Intel continually missed its own quoted dates throughout the last two and a half years, it kept talking about Larrabee, and often on the record, involving senior executives, via a steady stream of statements, SIGGRAPH papers and IDF briefings. Why do this? Surely someone knew Larrabee wasn’t hitting its targets – so either there was a political need to keep giving the project the air of publicity, or the desire to give Jen-Hsun Huang, Laughabee’s – sorry, Larrabee’s – most voluble critic a verbal smack in the chops.

Intel enjoys such a lead over AMD and has done for so long that it rarely bothers to directly address the competition in its media materials and public statements. The world of graphics is different. It’s always been combative and fiercely oppositional, often to the detriment of everyone involved. Instead of bringing across its own stately approach, Intel was suckered into childish smack-talk, once notably declaring Larrabee to be more efficient at rasterisation than a traditional GPU. Don’t forget the purchase of Havok either, which seems to have resulted in virtually no visible benefits for consumers. So, instead of being able to quietly forget Larrabee, the chip’s long public life has assured it an ignominious death.

Unlike Nvidia, which is aware of how it needs to expand its business, Intel’s dominance of the desktop and laptop CPU markets means it remains extremely secure. However, if I was an Intel shareholder, I would be a little worried by the inflexibility of approach the Larrabee project reveals about Intel’s attempts to get into new markets.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.